Community has become one of the buzzwords asscociated with coliving. But can a lifestyle real estate product that offers hospitality-like services and convenience at its core coincide with community building? Matt Lesniak of Conscious Coliving gives ULN his view.

In this article, we will look into these questions and debate whether coliving is more of a ‘community washing’ trend or a genuine way to foster community.

Community in real estate

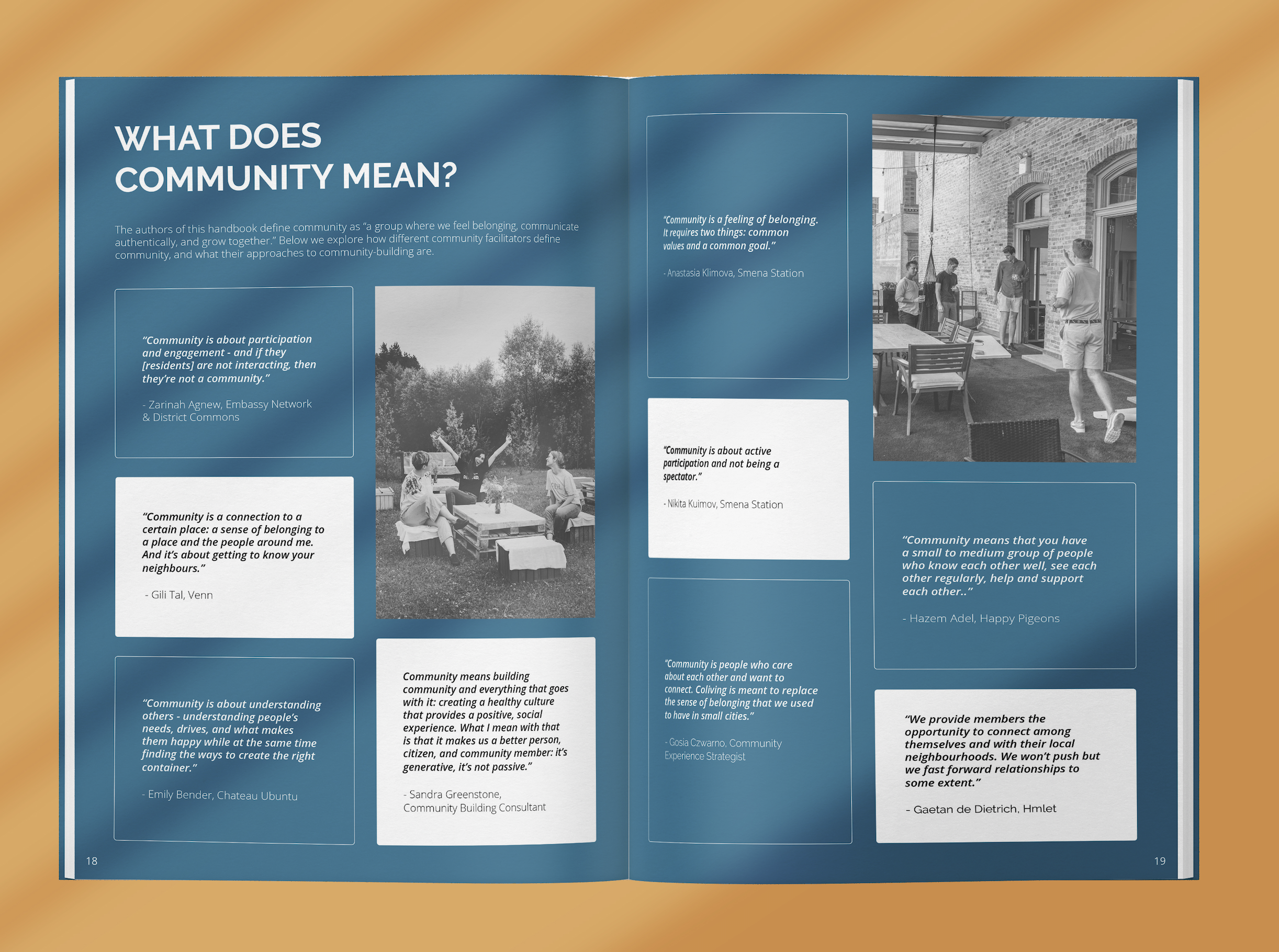

To start, we must define ‘community’. Conscious Coliving and Art of Co’s Community Facilitation Handbook states that community is a “a group where we feel belonging, communicate authentically, and grow together.”

The Handbook also highlights three essential components of a successful community, which include: shared values, psychological safety and sustained engagement. In other words, when people feel supported and safe enough to take risks, and they are aligned around shared interests and goals, they are more likely to participate in regular engagement and collaboration.

Furthermore, when thinking about levels of engagement in real estate projects like the development of a coliving space, a useful resource to consult is American sociologist Sherry Arstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. This ‘ladder of engagement’ represents the levels of agency, control and power citizens (or residents) have in regards to making important decisions in development, planning and even political processes.

The different levels of engagement range from nonparticipation (no power) to degrees of tokenism (perceived power) to degrees of citizen participation (actual power). In regards to real estate, one can think of how local communities and neighbours – and in the case of coliving, future residents – are involved in the design, development and operations of a certain scheme.

In real estate it is difficult to involve citizens / local community groups / residents in all of the decisions of the construction and operation phases, though there are a multitude of examples around the world of inspiring projects that have been co-designed with local stakeholders throughout the development lifecycle. For instance, Project for Public Spaces has a great framework of ‘What Makes a Successful Place’, which includes guidelines and frameworks for strong citizen participation, with their site showing dozens of successful examples.

Coliving operators also have an opportunity (and responsibility) to engage locals, future residents, staff and other stakeholders in the community building process. The next few sections will explain how.

Community in coliving

The Community Facilitation Handbook also defines different types of community approaches based on levels of participation, ranging from ‘Top-down Management’ to ‘Bottom-up Facilitation’. In the Top-Down approach, the operator imposes a vision of the community, its events, resident profiles, activities, and spatial and experience design. In the Bottom-Up approach, the operator involves the residents across all of these steps and usually the residents are highly involved in creating the overall experience themselves.

We’ve seen a mix of these approaches depending on the typology, size, location, target market and business model of specific coliving operators. Often operators have a blend of top-down management – when it comes to operations and facilities management for example – and bottom-up facilitation – for event management, for example.

The Handbook calls this a ‘Systems’ approach, which implies that the operator influences the user experience only to a certain degree, and is involved in guiding residents to be self-sufficient in organising their community – supporting residents via their community facilitators and community team, for example. These types of coliving communities give the opportunity for residents to have individual responsibility, run events and community assemblies by themselves, and where the operator is not actively involved in the day-to-day life of residents.

The main goal of the operator here is to take care of more administrative and operational tasks, as well as help residents in case of conflicts or maintenance requests. In theory, the residents take care of the rest. This type of community facilitation is currently quite rare within coliving, given its ‘service approach’, but when it does occur, it is typically found in smaller to medium sized communities, especially more rural and nomad coliving communities.

Community vs convenience paradox (and other community building challenges)

On the other hand, one big community building challenge in the coliving sector is the ‘community vs convenience paradox’: the more convenience a space offers, the less involved residents are, and hence less community.

When coliving operators only have a service layer approach within their experience (e.g. daily cleaning, top-down events programming, 24/7 reception, etc.) and lack opportunities for bottom-up engagement, this disincentivises residents to take responsibility for the space.

This creates a double edged sword scenario: the more service layers provided, the more residents put the responsibility of taking care of their home on the operator and the less they take ownership within the community. An easy example is the tragedy of the commons that occurs in (and around) the kitchen sink: with daily cleaning services in the shared kitchen, residents often get accustomed to just letting the cleaning staff take care of their dishes…

Other community building challenges include mismanaged and unclear expectations, weak onboarding and curation processes, lack of standard operating procedures (SOPs) and misunderstanding / undervaluing the role of the community facilitator.

Community facilitation or community washing?

With these community building challenges in mind, we have to ask whether or not authentic community building and engagement can occur in coliving spaces.

Critics of coliving often say coliving operators are mostly just ‘community washing’, and that these spaces don’t provide the same levels of community/engagement as cohousing communities, neighbourhood associations, community land trusts (CLTs) or bottom-up placemaking initiatives like the ones mentioned earlier.

The coliving model is a hybrid between hospitality, student accommodation/PBSA, built to rent, and coworking with elements and origins of intentional communities and cohousing. Coliving operators provide hotel-like services and convenience (e.g. all-in-one bills, fully furnished private rooms, etc.) as well as opportunities for personal and professional growth through events, social initiatives, wellness services and more. It is a residential real estate product that has elements of lifestyle, convenience, sustainability, community, wellbeing, technology and more.

That said, to those more accustomed to grassroots community building with high levels of participant engagement it may feel more like a hospitality brand with ‘all convenience and no community’.

To many others (especially colivers themselves) it may be their first time living communally with potentially hundreds of individuals with a multitude of traditions, ethnicities and backgrounds. The opportunities to exchange skills, learn about new cultures, contribute to events, meet new friends and potentially grow both personally and professionally are very present in coliving communities.

Coliving differs from more ‘high engagement’ community models in that it offers its residents a choice: residents can choose to stay in their own private rooms / comfort zones and just benefit from the convenient services provided, but they can also choose to join a plethora of events and other ways to contribute to the community.

For many people moving into a new city or travelling abroad, it may feel intimidating to join events or meet new friends. With the lighter touch ‘invitations’ coliving operators offer, these kinds of ‘first steps of interaction’ can be supported by structures coliving spaces put in place, including their community facilitators and their in-house community apps. Add in opportunities to exchange around shared interests / values and opportunities to resolve a few collective challenges, and you start to achieve the elements of a successful community mentioned above (psychological safety, shared values and sustained engagement).

To the point above, I do not deny the risk (and presence) of community washing in the coliving sector and I strongly believe that for coliving communities to thrive the appropriate structures need to be in place. This means creating strong expectation management, user and community experience (UCX) strategies, onboarding and curation processes, valuing community facilitators and their boundaries / personal resources and making sure your operations are running smoothly … if the elevator in your building doesn’t work for months, you can say goodbye to any chance of customer satisfaction and your vision for a thriving community.

This requires both significant human and financial resources, staff training, and taking care of staff wellbeing (so they can ultimately take care of resident wellbeing and satisfaction). Without these structures in place and without investing appropriately into your community, then the risk of community washing – and ultimately lower customer satisfaction and retention and higher resident and staff churn – is quite high.

Coliving brand, space, asset, scheme or community?

With all the different coliving variations on the market and with more to come in the next few months and years, it can be difficult to understand the approach operators are taking. Some are in the market for the more traditional ‘coliving is a real estate investment’ approach, some are going for more of a lifestyle product, and others are building what resembles more of a grassroots intentional community with elements of convenience and services suitable for the post-covid digital nomad or young professional.

For us at Conscious Coliving, the standard for quality coliving should have community, wellbeing and sustainability at its core, with an ESG/stakeholder-driven approach that positively benefits residents, local communities, cities and the planet. With the market in its consolidation phase, there are maybe only a few dozen conscious coliving operators, though we aspire to set the standard with the Conscious Coliving Manifesto and our courses, content, research and other services.

In the meantime, some market players may continue to operate (and perceive) coliving as a real estate brand, others as just a rental development or scheme, and others as a shared living community.

Does coliving foster community?

So does coliving really foster community? Many coliving communities absolutely do foster community. Other coliving brands that may not be putting community at the forefront do not as much, and sometimes suffer with harsh public reviews, anti-social behaviour, damaged properties and ultimately weak customer satisfaction and people going to live elsewhere.

The economic, environmental and social value of community is clear but the industry lacks in-depth and peer-reviewed market research to prove its benefits. Until we have clearer operational data and independent research, then community may continue to be a ‘nice-to-have’ or worse, a branding mechanism.

So yes, coliving does foster community, but market players can go even further in fostering shared living communities with purpose, people and planet at their core. With an extra push for individual engagement and maybe a collective challenge once in a while (washing the dishes together, for example), I think coliving operators and their community members can definitely get there.

Matt Lesniak is co-founder and head of impact & innovation at Conscious Coliving